You’re invited.

To what? To think. To participate, to live, and to understand your whole life will never be enough. But as Neil Gaiman’s Death says, “You get what anyone gets… you get a lifetime.”

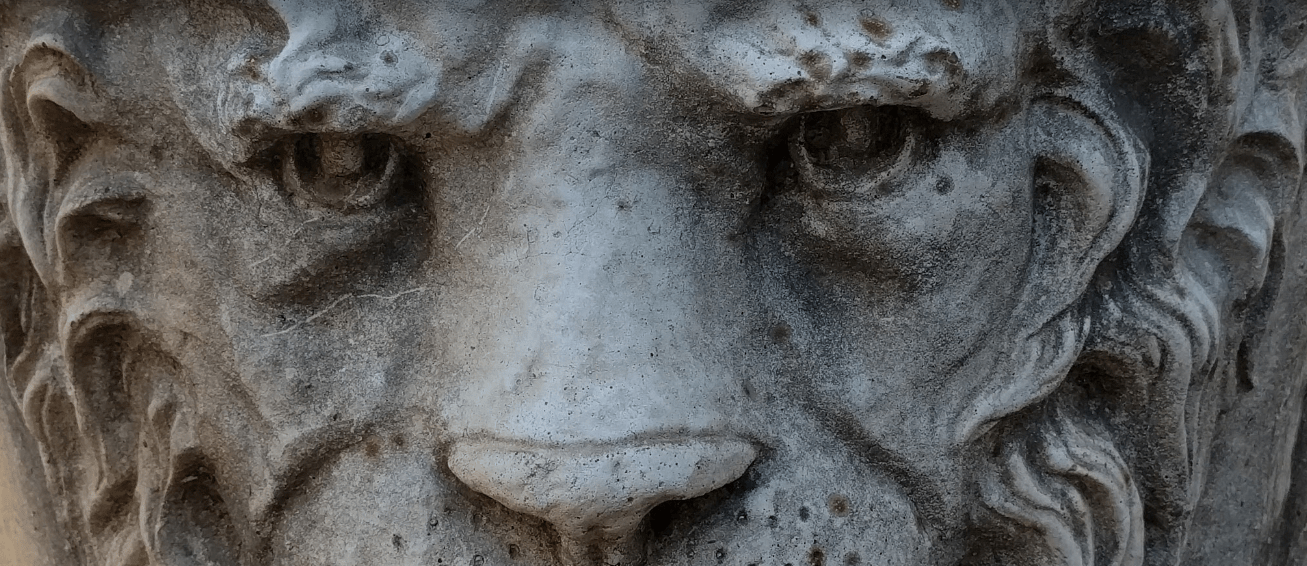

So: I promise not to waste it. Mine or yours. We have work to do. We have brains; it’s in our species designation, Homo sapiens. We happen to be the only surviving members of our genus. If I sound a bit grim, you can’t say you weren’t warned – it’s in the name: Skeleton At The Feast. Ancient Egyptians (the original Goths, with a better eye for color) reportedly gave skeletons a place at the dinner table, with an eye towards reminding partiers of mortality. (As if the pyramids and the entire mummy-industrial complex weren’t enough. These people were thorough.) The Romans, a cheerful lot noted for their subtlety, appropriated this custom and replaced the genuine article with small silver skeleton-shaped party favors called larva convivalis. Cue the nineteenth century: hygiene was in and silver was expensive. Therefore the custom was relegated to literary motif, and used by several Romantic poets including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (see The Old Clock On The Stairs, 1846).

Presently, it’s a phrase used to describe a grim reminder at a festive occasion.

I’ve always thought the quiet little critters had the best seat in the house, though. They get to see everything. They never make conversational faux paux. They are exempt from rules about which fork to use, and they never, ever have to worry about the morning after. They are observers, and they can be truthful because, seriously, no one is going to contradict them. And if someone does, they get the ultimate retort: a grin and a really meaningful stare.

You could say I consider them a role model.

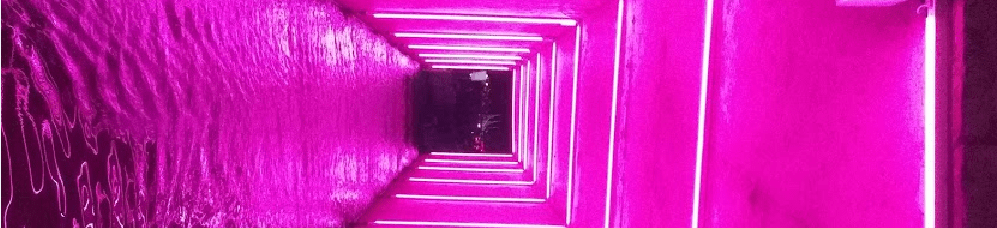

Here’s their invitation: give your time like a gift, because it is. Give it generously to places and creatures and moments that are important. There’s work to do, and the things you think about are too important not to change for the better.

Let me do you the favor of never wasting your time.

I’ll ask for your heart, which is rather a lot upon first meeting;

I might take your breath, but it’s a fair trade.

You give me voice.

You give me the person I want to be,

The one unafraid to laugh

And be outrageous; laugh at herself

And the world.

The one who speaks her mind, all nine of them.

The one with eyes so clear her brain shines through

And her heart remembers why it keeps beating.

Referenced: https://wordhistories.net/2016/09/07/a-skeleton-at-the-feast/